Preface to The Silmarillion: The Waldman Letter

The Waldman Letter

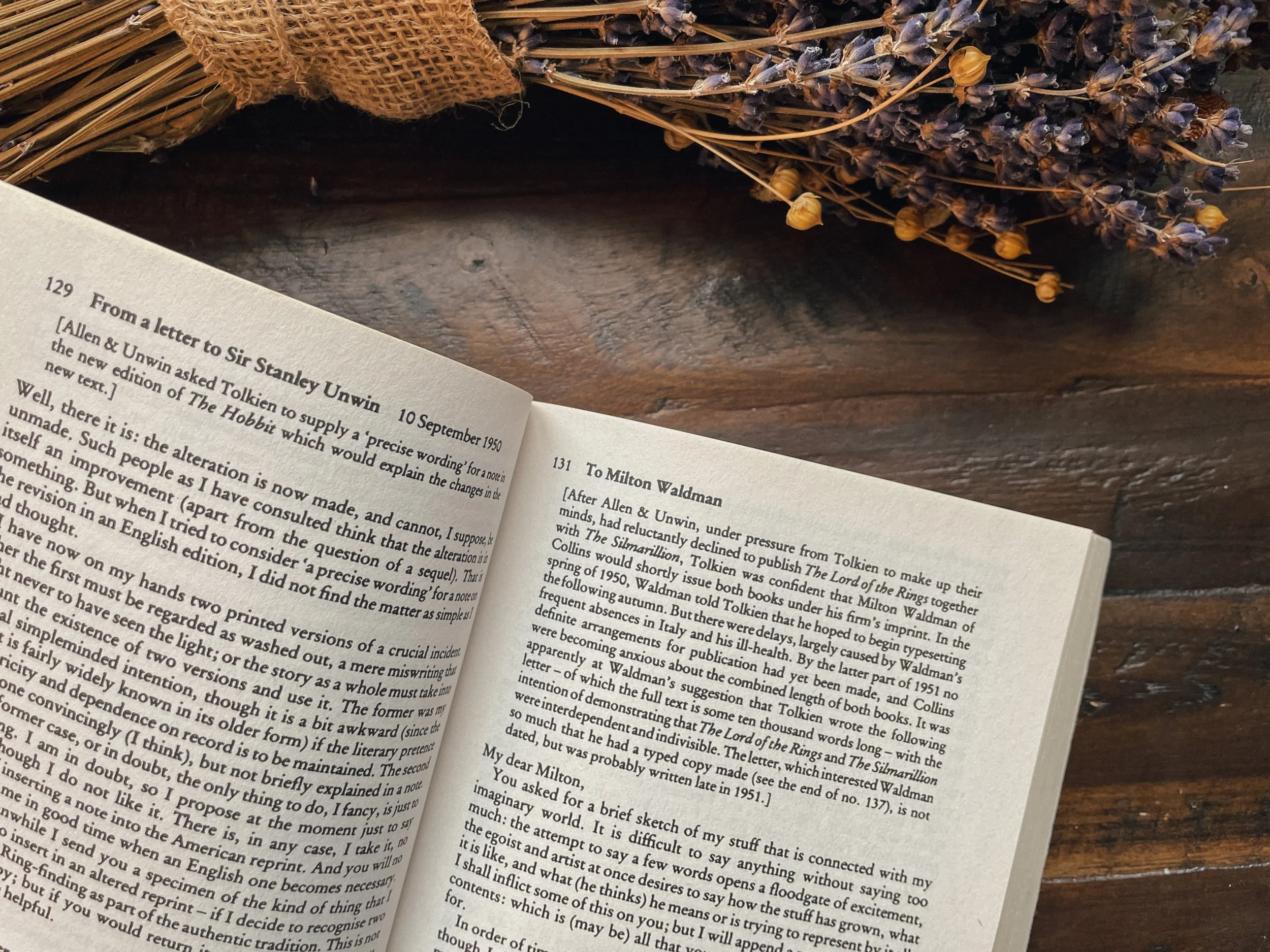

The Waldman letter is a letter written to Milton Waldman, an editor and advisor to publishers in London, who had expressed an interest in The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion after the widespread success of The Hobbit. For context, The Hobbit was published in 1937, this letter was written in 1951, and The Fellowship of the Ring would not be published until 1954. Unfortunately, The Silmarillion itself was not published until 1977 after Tolkien’s death.

Tolkien had hoped to publish The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion together and this letter reflects his belief that the two were interdependent. This letter is important because it pieces together all of Tolkien’s stories concerning Middle-earth, showing how they are all a part of the same “great tale”.

Reading Resources:

Please note: the letter as a whole seems to only appear in The Letters of JRR Tolkien, where it’s greatly abbreviated in all other sources I’ve found.

Brief Summary

Tolkien writes that he can’t remember when he wasn’t building his imaginary world or its languages, noting that almost all the names in his world are derived from these languages. This gives his works a specific kind of consistency that others may not have. He has always been passionate about myth, desiring a myth that could be uniquely English.

The three major themes of his works are Fall, Mortality, and Machine.

There is a distinct difference between the magic of the Elves (which he calls Art) and the magic of the Enemy (which he calls Machine).

After this, Tolkien then launches into a summary of his world’s history, from its creation all the way through its Third Age.

Detailed Outline

Please Note: this letter contains spoilers for the plot of The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien begins with an explanation as to why he’s writing this letter, which allows us a bit more context. He writes, “My dear Milton, You asked for a brief sketch of my stuff that is connected with my imaginary world…”

Tolkien has always been building his imaginary world and language for as long as he can remember; these languages are at the heart of his Legendarium.

At the same time, an “equally basic passion” of Tolkien’s was myth, fairy-story, and heroic legend. Because of this, he had hoped to create something uniquely English and dedicate it to his country.

Despite being a devout Catholic, Tolkien notes that he felt it was fatal for the Arthurian myths to explicitly contain Christianity within its myth.

“For another and more important thing: it is involved in, and explicitly contains the Christian religion. For reasons which I will not elaborate, that seems to me fatal. Myth and fairy-story must, as all art, reflect and contain in solution elements of moral and religious truth (or error), but not explicit, not in the known form of the primary ‘real’ world.”

Tolkien goes on to explain that it was once his vision to create an entire body of myth which he could dedicate to his country.

He describes how he would like to present this body of work, drawing some of its tales in their fullness while leaving room for others to contribute along the line. This line is often cited when the topic of adaptations comes up, so it’s a good one to pay attention to.

“I would draw some of the great tales in fullness, and leave many only placed in the scheme, and sketched. The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama. Absurd.”

He also explains that he feels the stories within his Legendarium arose as “given” things; he never felt he was inventing this world but rather recording its history.

After all of this out of the way, Tolkien gets into the major themes of his “stuff” as he calls it:

“Anyway all this stuff is mainly concerned with Fall, Mortality, and the Machine.”

Tolkien explains his usage of the word ‘Machine’ as it relates more closely to our modern usage of the word Magic.

“The Machine is our more obvious modern form though more closely related to Magic than is usually recognized.

The Magic of the Enemy vs. the Magic of the Elves

The Magic of the Enemy is this, “bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills.” Whereas the Magic of the Elves is a cooperation or even fulfillment.

The Magic of the Elves is Art.

He writes that, “Their ‘magic’ is Art, delivered from many of its human limitations: more effortless, more quick, more complete… And its object is Art not Power, sub-creation not domination and tyrannous re-forming of Creation.”

This motivation is seen throughout the different incarnations of evil throughout the Legendarium:

“The Enemy in successive forms is always ‘naturally’ concerned with sheer Domination, and so the Lord of magic and machines; but the problem: that this frightful evil can and does arise from an apparently good root, the desire to benefit the world and others -- speedily and according to the benefactor’s own plans -- is a recurrent motive.”

He then dives into a discussion of the mythology he has written in its chronology, beginning with the Music of the Ainur.

We have the creation of the world through music, and then the story moves onto the Elves (and eventually Men). Don’t forget the Dwarves, too!

As Mortality is one of the major themes, Tolkien explains the way that immortality works for the Elves and how it’s different from the gift of men (death).

“The doom of the Elves is to be immortal, to love the beauty of the world, to bring it to full flower with their gifts of delicacy and perfection, to last while it lasts, never leaving it even when ‘slain’, but returning -- and yet, when the Followers come, to teach them, and make way for them, to ‘fade’ as the Followers grow and absorb the life from which both proceed. The Doom (or Gift) of Men is mortality, freedom from the circles of the world.”

The focus of the Silmarillion, and the perspective from which it's told, is of the Elves.

Tolkien introduces the Fall which allows his story to begin.

“In the cosmogony, there is a fall: a fall of the Angels we should say. Though quite different in form, of course, to that of Christian myth.”

This Fall is different from other myths though it must “inevitably contain a large measure of ancient wide-spread motives of elements. After all, I believe that legends and myths are largely made of ‘truth’, and indeed present aspects of it that can only be received in this mode…”

Tolkien argues that there cannot be any ‘story’ without a fall, saying “all stories are ultimately about the fall”.

In this story, the Elves have a fall which comprises the main body of the Silmarillion proper; but Tolkien notes that the first fall of Men does not appear in The Silmarillion.

The basic story of the Elves is then told: the exile of the Noldor (“the most gifted kindred of the Elves”), their re-entry into Middle-earth, and their strife with the Enemy.

This continues through the ending of the Silmarillion proper and with it, the First Age.

The Three Themes of the Second Age:

The Delaying Elves

Sauron’s growth as a new Dark Lord

The Fall of Númenor

Sauron’s influence on the Elves in the Second Age:

“But many of the Elves listened to Sauron. He was still fair in that early time, and his motives and those of the Elves seemed to go partly together: the healing of the desolate lands. Sauron found their weak point in suggesting that, helping one another, they could make Western Middle-earth as beautiful as Valinor.”

Tolkien writes about the Ring-verse and its connection to the story as a whole.

He walks the reader through the strengths -- and weaknesses -- of Sauron as he has poured so much of his own strength into this physical object. Ultimately, he has really weakened himself through this act of hubris which will lead to his downfall.

“Also so great was the Ring’s power of lust, that anyone who used it became mastered by it; it was beyond the strength of any will (even his own) to injure it, cast it away, or neglect it. So he thought. It was in any case on his finger.”

The Downfall of Númenor

The downfall of Númenor is really presented as a result of their response to the Ban of the Valar. Rather than accepting mortality as a gift, they see it as the denial of something good -- something which, perhaps, they deserve. Perhaps they are even owed it, they begin to think.

Tolkien writes that “their reward is their undoing – or the means of their temptation.”

He then explains that there are three phases to their fall.

When Sauron brought to Númenor, he comes as a prisoner but quickly worms his way into the ear of the King.

Here we get to a slight discrepancy between the Letter and the Akallabêth so I just want to clarify that this must have been a change that was ultimately made in Christopher’s compilation of his father’s notes etc.

The letter refers to “Tar-Calion the golden, thirteenth king in the line of Elros”; Tar-Calion would have been Ar-Pharazôn’s name if he would’ve adopted a Quenya name, but he also ended up being the 25th ruler of Númenor and not the thirteenth so just keep that in mind.

Tolkien writes of the New Religion which emerged in Númenor under the direction of Sauron, which ultimately led to the breaking of the Ban of the Valar, the destruction of the island of Númenor, and the Reshaping of the World.

The Survivors of the downfall fled to Middle-earth to start anew, ultimately joining in the Last Alliance against Sauron. Sauron is apparently vanquished and the Ring is kept by Isildur as a weregild, a recompense for all that he had lost to Sauron.

The Third Age begins with the diminishing of the men of Númenor in Middle-earth as their realms are weakened and divided.

Hobbits begin to appear in history in the middle of the Third Age

Tolkien recounts the story of The Hobbit, and then describes its “sequel”, The Lord of the Rings.

He notes the difference in tone and perspective between The Silmarillion, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings.

Finally Tolkien ends the letter by writing, “I wonder if (even if legible) you will ever read this ??”